John Romero wants you to know he was abused. It's the main topic of the very first chapter of his autobiography. His early childhood was marked by great financial hardship, exacerbated by his father's addiction to drinking and gambling. Romero Senior beat his wife and both his sons. One day in blind, intoxicated rage, he drove his 6 and 4-year-old offspring into the middle of the sweltering desert and abandoned them. John Romero's father would ultimately drink himself to death.

“'He's a Romero,' my Mom sighed. 'He's going to be a loser just like his dad.'”

The step-father John Romero lived with later was a better role model, but a strict one. He expressed his dissatisfaction with the young Romero's addiction to arcade games by smashing his face into the screen of an Asteroids machine. Later that day he punched Romero square in the face. On a more positive note, this step-father would later buy the young Romero an Apple II. With the gift of that powerful tool the ascent of a true rock star of game development began.

Only the misinformed would dismiss John Romero as a foppish poser riding on John Carmack's coat-tails. He was an accomplished coder and game designer long before co-founding id Software. His troubled upbringing gifted him with a sense of desperation which drove him to master assembly programming, first on the Apple II, and then on PC.

At id John Romero collaborated with luminaries John Carmack, Adrian Carmack (no relation), and Tom Hall on such pivotal games as Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, and Quake. This Dev Dream Team redefined gaming as we know it. Before id, there were no first-person shooters, death-matches, or even game engines. They blazed the trail.

Yet Romero would ultimately be expelled from the studio he co-created, thanks to interpersonal conflicts that, at the time, seemed insurmountable. Romero believes his greatest failure was his mishandling of his professional relationship with the eccentric and determined John Carmack. Romero's career survived the rift, but you can tell their falling out torments him, even now.

I was astonished to read what little terrors both the Johns of id were in their teens. John Romero once took his father's rifle and shot out the windows of the other caravans in his trailer park. At the age of 14 John Carmack synthesised thermite and used it in a failed attempt to steal computers from his high school.

John Carmack comes across as a powerful yet distant intellect. Clinical. Ruthless. When his pet cat pissed all over his expensive new leather furniture, John Carmack promptly got rid of it. When Tom Hall's early ideas for Doom didn't gel with the direction they ultimately took, Carmack promptly terminated him. Carmack issued 'Report Cards', callously grading the perceived job performance of his early id colleagues, even though they were all working just as hard as he was.

“You are only as good as your last game, no matter who you are.

This was a lesson I needed to learn.”

Romero makes it quite clear that Carmack inhabited a different mental and moral universe to his peers. At one point he bizarrely suggested that any shareholder fired should have the value of their shares halved for the purposes of calculating their payout. This was obviously aimed at Romero. Carmack had clearly made up his mind to terminate his trusted friend long before he resolved to quit.

It's telling that Romero refers to his co-founder throughout the text as 'Carmack', not 'John'. The two claim to have patched things up and that these days there is no animosity between them. I have my doubts. They have so much in common, but very different personalities. Were they ever really friends at all? I am reminded of that line in Alan Moore's Watchmen when Dr. Manhattan says that the World's Smartest Man is no more of a threat to him than the World's Smartest Termite.

After being forced out of id John Romero reunited with Tom Hall and founded Ion Storm. Its dysfunction and downfall are the stuff of legend.

Yet Romero takes responsibility for his failures. In collating the story of his life's work, he saw that again and again his reluctance to confront people cost him dearly. He attributes this to bad habits he learned as a battered child. Little John Romero would cower and hide from his beatings, knowing that his father's fits of rage would pass. But adult John Romero had chosen some incompatible business partners when founding Ion Storm, and the longer they worked with him the more damage they did.

On several occasions he trusted his gut, and his gut let him down. Like the time he decided to change engines midway through development of Daikatana, or when he thought it would be a good idea to call the main character 'Hiro Miyamoto.'

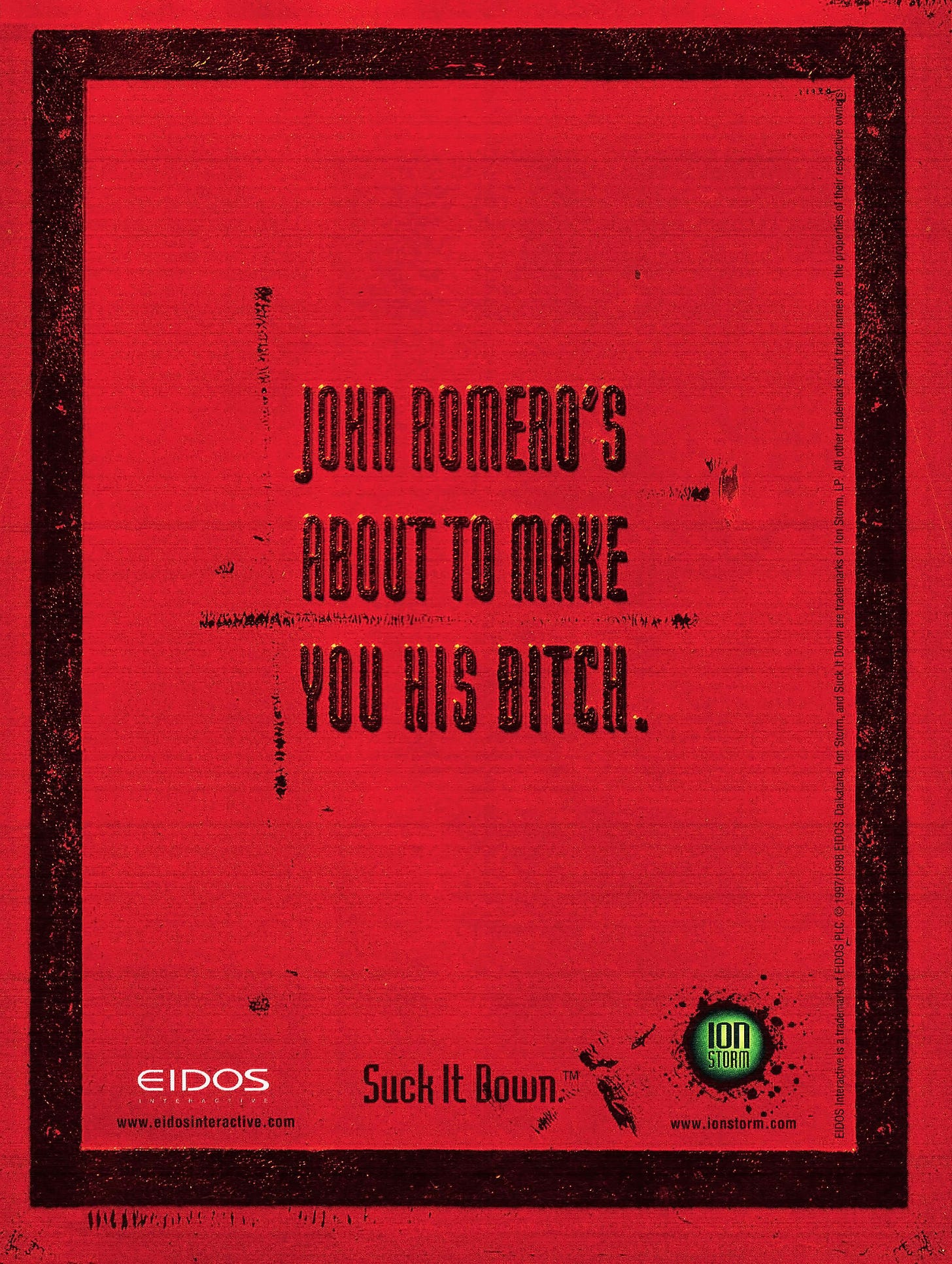

He made a tremendous blunder when he overruled his gut and approved 'The Bitch Ad'. Romero wants to make it absolutely clear that The Bitch Ad was NOT his idea, and that he signed off on it with great reluctance. Yet he did sign off on it, and gamers worldwide felt that their hero was tea-bagging them. The damage to his reputation was irreparable.

After Ion Storm Romero founded more companies, and made more games, but he never climbed back to the dizzying heights of stardom he attained in his 20s.

“It's a wild ride, most of it downhill... I own the trainwreck that was Ion Storm.”

Some career disasters were completely out of his control, like the time he sunk four years of his life into making an educational MMO before engine problems rendered the project unviable.

Apparently his port of Red Faction for the N-Gage was superb. But very, very few people bought Nokia's pioneering game-phone. He created a Facebook game that was a huge success. But Facebook gaming turned out to be a fad. Pure ephemera.

More recently there was a slow-motion train wreck called Blackroom. When Romero came up with the idea for a first-person shooter set in a VR game gone rogue, his consultants told him that his crowd-funding campaign wouldn't need a playable demo to succeed. They were wrong. When he actually did make a Blackroom demo to showcase to publishers, they all turned it down because the Kickstarter failed. Ouch.

Romero has created brand new levels for Doom in recent years, to great acclaim. He's working on a brand new blockbuster game, which as of this writing is unannounced. He's living a great life in picture postcard Ireland, and he has dedicated a lot of time and effort to the important work of preserving classic games. Yet there is something bitter-sweet about his evolution from a rock star into an archivist of his younger self.

After reading both Control Freak and Doom Guy, I see many parallels between the lives of Clifford Bleszinski and John Romero. Both are survivors of abuse. Both became obsessed with making games while very young. Both worked very, very hard. Both are self-made men. Both were extremely lucky in finding collaborators with which they could create pioneering software companies. Both ran out of luck when they founded their own studios. Both learned the hard way that game development and studio management require very different skill sets.

Another parallel between Control Freak and Doom Guy is that both authors spent as much space as possible chronicling the glory days, and then briskly skimmed over their career disasters. Romero tries to be diplomatic and vague, but you can read between the lines. There's the story of the Ion Storm employee who worked on his own project on company time, while filling up the gap between his cubicle wall and the side of the building with empty drink cans. This unnamed salary pirate acted so defiantly because he knew he could get away with it. He treated his boss with contempt.

“It never occurred to me that this was abnormal.”

Ask Iwata should be on any aspiring game developer's bookshelf. Doom Guy might be a useful companion volume, and not just because Romero shows what not to do. Readers will also learn the mindset behind his winning formula for level design. Romero explains how the architecture at Disneyland inspired his map layouts, how he strives to give each level a sense of pacing, something akin to a roller coaster ride.

He stresses the importance of resilience, given the fact that every career will have highs and lows. Above all, readers will learn why management problems must be faced head-on as soon as they're detected. Any company with festering wounds will sicken and die.

There are only a handful of typos, but they're distracting. Typos always are.

Doom Guy is a comprehensive, if pedestrian catalogue of the career and works of John Romero. He owns all of his mistakes, even if he writes as though he was at times but a helpless bystander to his own life. He does his best to squash baseless long-standing rumours and endeavours to answer any potential fan questions. For instance: Why did id Software stop making Commander Keen games? Simple: They got bored. Tom Hall's feelings were hurt, but it was necessary for them to grow as a company, and as creators. Their internal motto in those days was: 'We are the wind.' Their instinct was always to explore new horizons. To soar to new heights.

“When will my next shooter be released? When it's done.”

The book is exhaustive, and at times exhausting to read. Yet Romero didn't include absolutely everything. Stevie Case is only mentioned once, exactly once, in the entire book. This surprised me. I recall Ms. Case and Mr. Romero being quite close, professionally. She worked under him in a variety of positions, learning the ins and outs of the games industry.

With his splendid near-photographic memory, we can only assume that any aspects of his personal history missing from this work are deliberate omissions. Now might be a good time to re-read Masters of Doom to fill in the blanks...